Sin Titulo is a rare kind of graphic novel, a mad combination of noir thriller, Lovecraftian myth and Matrix-style philosophy. Released over a period of five years before finishing in 2012, the graphic novel brings the entire story together in 166 good quality pages of mood-infusing content. Cameron Stewart has worked on Batman & Robin, The Other Side and Assassin’s Creed as a very talented artist, but used Sin Titulo (which literally translates to “no title”) to become more comfortable with the process of writing – and to satisfy the creative urge to make a story of one’s own.

An under-appreciated but complacent proof reader is shocked out of monotony by finding that his grandfather had passed away a month ago and he hadn’t been told – it makes him sickeningly aware that he had neglected visiting his grandfather. When he finds a photograph of his grandfather smiling with a young and beautiful woman, he becomes obsessed with figuring out this mystery, at the expense of his safety and sanity.

The initial set-up of the grandfather passing is something that happened to Cameron Stewart, and the graphic novel’s central image of the figure sat underneath a tree is something Stewart dreamt one night, and hastily drew the next day. When he started writing Sin Titulo, he had no idea where it would go, relying on instinct only as a kind of improvisation exercise – it was his unbridled creative outlet, with no plan but ideas for for future scenes until the last twenty or so pages that aimed to wrap the story up.

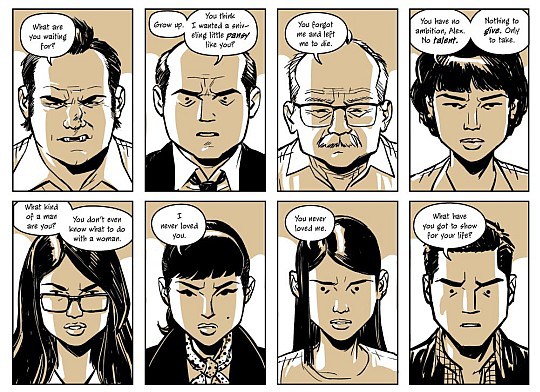

When you first open the cover of Sin Titulo, you find yourself being glared at by a sequence of disappointed and angry faces – it gets the reader into a great mindset and I think helps to understand the kind of guilt Alex is feeling. It begins with “I’ve been having a dream…” and Alex walking along the dreamworld of the beach and tree – I love the detail he remembers, his bare feet sinking into the coarse sand, just as dreams can still feel real when you have woken up.

The residential care home where his grandfather lived is like a paranoid dream – no one is giving him any answers, the receptionist talks like Alex isn’t even there, and a sexually aggressive orderly seems to haunt every corner. Seeing the image of his grandfather and the young woman, he realises that never saw his grandfather happy, only ever crying and wishing he was dead, and the realisation makes him feel even worse about not visiting. He dreams the night of that same beach with the dead tree, but now the figure under the tree is the woman from the photo, and when she lowers her sunglasses there are maggots rotting where her eyes should be – it’s such a visceral image and the “plep”, “chlop” and “slup” noises only add to the horror.

Everything’s starting to fall apart for Alex. As his obsession grows and centres around the violent orderly, Wesley, he follows the man at the end of his night shift, ignoring the pleading of his girlfriend. The radio is talking about the end of the world and callers are making discriminatory remarks, a homeless man propositions Alex and rapidly becomes violent, and the receptionist in the building he has found appears to be discussing having an abortion on the phone while dealing with him. It’s all just ever so slightly unnerving.

Remembering the inscription on the back of the photo, Alex thinks quickly and acquires the key to a room containing only a television, phone and chair. The phone rings and he picks it up only to see himself, sat in that room, on the TV and looking up sees there is no security camera – at least none that he can see. When the woman from the photo appears on the screen, she asks him to recall a memory. This is the first of the flashbacks which add up to this person Alex has become, and the first time we see the hideous creature which scared him as a child, leading to an argument between his father and grandfather. I would assume that this was a vital part in the separation of Alex from his grandfather. When Wesley finds him in the room, he beats him mercilessly, takes his keys and pulls out a syringe; next thing Alex is waking up at the side of the road with blood streaming from his nostrils.

Things just keep getting worse for Alex: the harder he tries to get out of his situation the worse he makes it, and it’s not long before he’s lost his girlfriend, his job, and an angry outburst against Wesley with a fire extinguisher escalates rapidly into the murder of two police offers who have been “torn apart”. There’s something seriously wrong about Wesley, and Alex seems sure that he is the key to this mystery which is really all he has left in his life.

Things get progressively more surreal at the story goes on; one of the particularly horrible pages features a dream in which a freakish lobster-type creature sprays burning ink into his face. The “skltch” sound effect really drives it home. In the real world (is it?) he meets a man who knows the image of the dream, who dreams it too and obsessively paints it.

The flashbacks are probably my favourite part of Sin Titulo because of their detail. Together they add up to this dysfunctional person – his aggressive father drunkenly punishing him for nothing, for being a child, his sexual and emotional inadequacies, his own selfishness. A dreamlike summer in Paris in which he falls in love with a beautiful young woman is spoiled when she visits him in America and they end up sleeping as far apart as they can, barely talking – it was only a simulation of happiness. He remembers his boss drunkenly seducing him at a party, and he turns her down for all the right reasons but she’s hurt, and he feels emasculated and guilty. When he finds out that Carrie hadn’t been happy for a while in the relationship it’s just one more blow to deal with.

The downward spiral that Alex falls into, the paranoid delusions and terrifying are dreams are pure Lynch; or Daniel Clowes if you’d prefer a literary reference. It deals with masculinity in a similar way to Fight Club, where expectations of “what a man should be”, instilled by an abusive and emotionally absent father lead to an advanced state of adolescence. His admission that he began looking into the photo and following Wesley because it would make a good story is a hard moment – he’s not a bad person, but maybe he’s not as good as he thought either. This is all reinforced by those images of the disappointed and angry faces in the front and back of the book.

It becomes a lot more philosophical toward the end of the book with questions about the nature of reality. The dream space of that beach with the figure under the tree changes and evolves and becomes more real – it lives in the space between the number, where “clarity breaks through the noise”. Alex becomes the monster in his own dream, the bad influence of his childhood, a self-fulfilling prophecy. It’s sad, and scary.

There are so many parts of the book that I could talk about, from tiny details in the lettering and gruesome “sound effects” to the textures of the dream which, like the Black Lodge of Twin Peaks, is there and not there. Reflections of Alex are used several times, in television screens and sunglasses, suggesting self-examination on his part. We see this man pushed to the limits of sanity and over, and it’s thrilling. A fantastic piece of work collected into a beautiful hardback book.

Cameron Stewart will be appearing at this year’s Thought Bubble, so grab your copy and get it signed. That’s what I’ll be doing!